The International Court of Justice has resolved over 110 disputes since 1945. This makes it the world’s most influential judicial body. The prestigious court operates from the Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands, and serves as the only judicial institution that resolves disputes between all 193 UN Member States.

The sort of thing I love about the court is its unique structure. Fifteen judges serve nine-year terms and work in both English and French. The court’s judgments remain final and binding, but it can only hear cases when states ask for its intervention. Its advisory opinions, while not legally binding, shape international relations and state behavior significantly.

This piece explores how the International Court of Justice operates, from its jurisdiction to its decision-making process. You’ll learn about the court’s role in global peace, its approach to contentious cases, and the challenges it faces when enforcing decisions.

The Structure and Jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) has a unique structure and jurisdiction that makes it different from other international institutions. This 78-year-old principal judicial organ of the United Nations works within a framework that balances representation, expertise, and authority based on consent.

15 Judges from Around the World: Selection and Composition

The ICJ’s heart consists of 15 judges elected for nine-year terms by both the UN General Assembly and Security Council. Elections happen every three years for five judges to keep the Court’s knowledge intact while bringing fresh perspectives to the bench.

The selection process needs careful thought. Each candidate must get absolute majority votes from both the General Assembly and Security Council. National groups in the Permanent Court of Arbitration propose candidates instead of direct government nominations. These groups can suggest up to four candidates, with no more than two from their own nationality.

Judges must be highly qualified—they should either meet requirements for their country’s highest judicial positions or be known experts in international law. The Court must also represent the “main forms of civilization and the principal legal systems of the world”. This requirement leads to an informal geographic split:

- Five seats for Western countries

- Three for African states

- Two for Eastern European states

- Three for Asian states

- Two for Latin American and Caribbean states

Judges work as independent magistrates rather than country representatives. They must make a solemn declaration to be impartial and conscientious before starting their role. Their annual salary is USD 191,263 plus post adjustment as of 2023, and the President gets an extra USD 25,000.

Types of Cases the ICJ Can Hear

The Court deals with two main types of cases:

Contentious cases: States voluntarily submit legal disputes. These cases can only involve states—individuals, corporations, NGOs, and other entities cannot participate directly. Court decisions become final and binding without appeal.

Advisory opinions: UN organs and specialized agencies ask the Court for legal guidance. These opinions serve as advice rather than binding decisions, yet they shape international relations significantly.

The Court uses several legal sources for contentious cases:

- International treaties and conventions in force

- International custom

- General principles of law

- Judicial decisions and qualified publicists’ teachings as backup sources

How States Accept the Court's Authority

States must agree to the ICJ’s authority—no one can force them to appear before the Court. They can show this agreement in four ways:

Special agreement (compromis): States come together to bring a specific dispute to the Court.

Jurisdictional clauses in treaties: States that sign treaties may allow the ICJ to resolve disputes about interpretation or application.

Optional clause declarations: States can accept the Court’s mandatory jurisdiction when dealing with others who do the same. By June 2023, 74 states had active declarations.

Forum prorogatum: States might accept jurisdiction after someone starts proceedings against them, even without prior agreement.

States can challenge the Court’s jurisdiction through preliminary objections. The Court then decides if it has authority before looking at the case details.

The ICJ remains a consent-based institution that gets its power from sovereign states’ willingness to resolve disputes through judicial means. This feature, combined with its diverse judges and dual jurisdiction, shows how international justice works at its highest level.

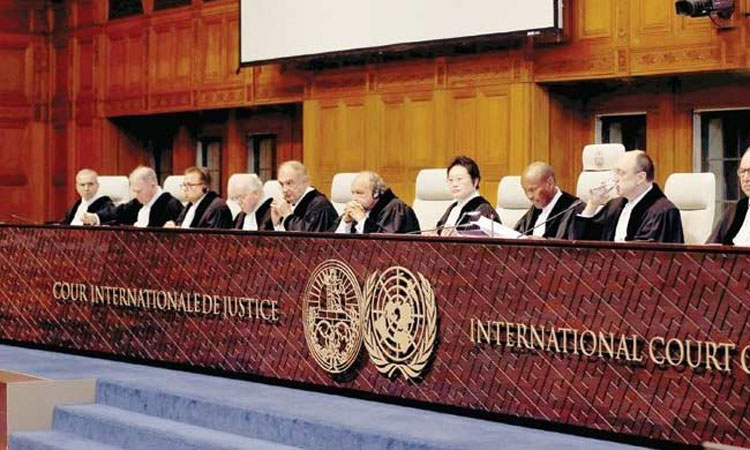

Inside the Peace Palace: Where Global Disputes Are Heard

The Peace Palace stands as an architectural masterpiece in the heart of The Hague. This magnificent building serves as the epicenter of international justice. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) – the United Nations’ main judicial body – operates from here, resolving global disputes through legal channels.

The Physical Setting of International Justice

The Peace Palace makes a powerful statement with its granite, sandstone, and red-brick exterior. The building showcases neo-renaissance architecture designed by French architect Louis Cordonnier. Construction took place between 1907 and 1913, with the building first housing the Permanent Court of Arbitration. The ICJ has made this prestigious location its home since 1946, taking over from the Permanent Court of International Justice that operated there from 1922.

The building sits on seven hectares of beautifully landscaped parkland in central Hague. Symbolic statues of justice and peace grace the façade. The left side features a clock tower that reaches 80 meters high. Swiss craftsmen gave the clock that sits atop the highest tower. A carillon with 48 bells fills the air with music every Tuesday and Thursday from 13:00 to 13:45.

The Palace’s interior showcases extraordinary materials:

- Diverse marble varieties

- Intricate woodwork

- Decorative glass

- Elaborate ceramics

Dutch artists wove natural motifs with ancient symbols of peace and law throughout the interior. Two towers mark the locations of great and small courtrooms where international justice takes place. The Court’s Deliberation Room and member offices found their home in a new wing built in 1978, with more additions coming in 1997.

The building’s motto “Peace through Law” comes alive through various objects and images. Hermann Rosse, a young interior designer of just 24, worked with Dutch designers to create spaces that speak to international justice’s mission.

Court Officials and Their Roles

The Court operates with a clear hierarchy of officials. Fifteen judges form the core panel, each elected to nine-year terms by the UN General Assembly and Security Council. These judges choose their President and Vice-President for three-year terms.

States that appear before the ICJ work differently than domestic courts. They communicate through their Foreign Affairs Ministers or Dutch-accredited ambassadors rather than permanent representatives. Each state picks “agents” who act like solicitors with diplomatic power to represent their nation.

These agents play several key roles:

- Lead special diplomatic missions with state authority

- Get case updates from the Registrar

- Handle correspondence and pleadings

- Present opening arguments

- Submit formal documents

Agents often team up with co-agents, deputies, or assistants. They work with counsel who help prepare pleadings and deliver oral arguments. The Court differs from domestic systems as it has no special bar – governments just need to appoint their counsel.

Cases can move forward even if states fail to appear, provided the Court has jurisdiction. The Court might combine proceedings when parties in separate cases make similar arguments against the same opponent.

The Peace Palace stands as more than just a building. It represents international justice in physical form – a place where law, not force, settles global disputes.

How a Case Moves Through the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice follows a clear path from start to finish in its court proceedings. This process shows how diplomatic conflicts turn into legal cases that judges decide through judicial reasoning and international law.

Filing Applications and Special Agreements

States can bring cases to the Court in two ways. A state can file a case against another state that indicates the respondent’s name, what the dispute is about, and why the Court should handle it. The Registrar then sends this application to everyone involved, including UN Member States through the Secretary-General. Two or more states can also agree to submit their dispute together through a special agreement (compromis).

The case starts on the filing date. The case titles show how they began – applications use “v.” between party names like “Nicaragua v. Colombia,” while special agreements use a slash, like “Benin/Niger”.

Written Proceedings: Memorials and Counter-Memorials

The written phase starts after the Court accepts the case. This phase takes the most time and includes:

- Memorials: First written documents with facts, legal arguments, and evidence

- Counter-memorials: Response documents to the memorial’s claims

- Replies: Extra documents when needed

The Registrar handles all communications based on the Court’s schedule. Each side must give certified copies of their documents to the other side. These documents stay private until oral proceedings start, and even then, only if both sides agree.

The Ukraine v. Russian Federation case shows how much paperwork this creates. Many states filed written observations. The “Immunity from Legal Process of a Special Rapporteur” case saw several governments submit statements and comments.

Oral Arguments: What Actually Happens in Court

Public hearings happen at the Peace Palace next. The Court listens to witnesses, experts, agents, counsel, and advocates. The Court’s President leads these sessions, which use both English and French. Everything said gets translated between these languages.

Agents start by presenting their government’s case, followed by legal experts who give detailed arguments. The Court controls everything and decides how long each side can speak. The judges can ask for more documents or explanations anytime, and they note any refusals.

Deliberation Process: How Judges Reach Decisions

The President closes the hearing after oral arguments finish, and judges start private discussions. These talks stay secret. Judges meet first in the Council Chamber to discuss everything, and the President makes sure everyone shares their views.

Each judge writes down their position. They vote on all questions, and most judges must agree. The President breaks any ties. A team then writes the judgment, explaining the Court’s reasoning and listing which judges took part.

Judges must work through differences from their varied backgrounds and legal systems, which often makes cases take longer. The President and Registrar sign the final judgment and read it in open court with the agents present.

The Judgment Day: Decision-Making at the ICJ

The resolution of disputes between sovereign nations needs a careful process that weighs legal principles against diplomatic sensitivities. The Peace Palace becomes a sanctuary of private deliberations after the Court withdraws to make its decision.

Majority Opinions and Dissenting Voices

The International Court of Justice makes decisions through majority vote, and each judge must take part in the final decision. A tie leads to the President casting the deciding vote. The ICJ differs from many domestic courts by letting judges share individual viewpoints through separate or dissenting opinions when they disagree with what most judges conclude or how they reason.

These individual opinions play several vital functions in international jurisprudence:

- They state alternative legal analyzes that could shape future decisions

- They help clarify basic principles that consensus judgments might obscure

- They help develop international law through dialog

The Court stated in 1987, “To interpret or clarify a judgment it’s worth taking into account any dissenting or other opinions attached to the judgment”. Notwithstanding that, separate opinions don’t have the same formal authority as majority judgments, though they carry substantial weight.

Legal Reasoning Behind Court Decisions

The Court uses two main methodological approaches in its legal reasoning. The inductive method draws general rules from observable patterns of state practice and opinio juris. The deductive method creates specific rules from existing general principles through legal reasoning.

The ICJ rarely explains its methodology directly, yet its practice shows a complex mix of these approaches. One observer points out, “Methodology is probably not the strong point of the International Court of Justice or, indeed, of international law in general”. The Court mainly relies on induction, and turns to deduction when:

- Limited state practice makes inductive reasoning impossible

- A potential non liquet (gap in the law) might emerge

- Inductively-derived rules need confirmation

Research into the Court’s actual practice reveals that “the main method used by the Court is neither induction nor deduction but, rather, assertion”. This highlights how pragmatic international adjudication really is.

Remedies and Reparations Ordered by the Court

The Court applies the Chorzów Factory standard of full reparation when it finds a state responsible for an internationally wrongful act. This standard aims to “wipe out all consequences of the illegal act”. The ICJ can order several types of remedies:

- Declaratory judgments that explain legal rights and obligations

- Monetary compensation for material and moral damage

- Restitution to restore pre-wrongful act situations

- Satisfaction through formal apologies or acknowledgments of wrongdoing

The Court sometimes awards “compensation as a global sum, within the range of possibilities shown by evidence and taking into account equitable considerations” for complex cases with mass violations. The 2022 DRC v. Uganda case demonstrated this approach, with the Court awarding $325 million for damages to persons, property, and natural resources.

The Court’s assessment of reparations shows evolving standards of proof. The Uganda case revealed that “the standard of proof needed to establish responsibility is higher than in the present phase on reparation, which needs some flexibility”. The ICJ maintains high evidence standards and rejects claims that lack sufficient documentation or clear methodologies.

The Court balances several factors in its approach to remedies: the principle of full reparation, practical evidence limitations, and the need for fair solutions in complex international disputes.

Beyond Judgments: Other Dispute Resolution Tools

The International Court of Justice has several specialized tools that go way beyond the reach and influence of traditional judgments. These tools give the Court more flexibility within the international legal framework to respond to various situations that require judicial intervention.

Provisional Measures: The Court's Emergency Powers

The ICJ has the authority to indicate provisional measures when immediate action is needed. Under Article 41 of the ICJ Statute, the Court can specify temporary measures to “preserve the respective rights of either party”. These measures work like emergency injunctions in domestic legal systems.

The Court used these powers in the South Africa v. Israel case concerning Gaza recently. It ordered Israel to “immediately halt its military offensive” in Rafah to prevent potential irreparable harm. The parties and Security Council must receive notice of these measures once indicated.

Advisory Opinions: Influence Without Binding Force

Advisory proceedings let the Court address legal questions from authorized UN bodies, unlike contentious cases between states. Under Article 65, the ICJ “may give an advisory opinion on any legal question” requested by authorized entities.

Five UN organs and sixteen specialized agencies have this authority. The process includes written statements and public hearings that conclude with a public reading of the opinion.

These opinions carry “great legal weight and moral authority” even though they’re not binding. They serve multiple functions:

- Clarifying international legal obligations

- Contributing to the development of international law

- Acting as instruments of preventive diplomacy

Interpretation and Revision of Judgments

The Court keeps its authority to interpret or revise judgments under specific conditions after delivering them. Article 60 enables the ICJ to construe previous judgments when disputes arise “as to the meaning or scope”.

Article 61 allows revision if someone finds “the discovery of some fact” that wasn’t known when the judgment was made. Revision has strict limits though:

- The fact must be “of such a nature as to be a decisive factor”

- You must apply within six months of finding the new fact

- No revision after ten years from judgment

These supplementary mechanisms – provisional measures, advisory opinions, and judgment revisions – complete the Court’s toolkit to resolve international disputes beyond traditional judgments.

Enforcement Challenges: What Happens After the Ruling

The International Court of Justice faces unique challenges when enforcing its rulings in global disputes. Nations must legally follow judges’ verdicts, but no central authority can force them to comply.

The Security Council's Role in Enforcement

Article 94(2) of the UN Charter allows parties to seek help from the Security Council when others fail to follow ICJ judgments. The Council can “make recommendations or decide upon measures” to enforce the ruling. The Court depends on political negotiations between Council members because the Council has complete control over enforcement actions.

Unfortunately, any permanent member can block enforcement efforts. This became clear in the Nicaragua v. United States case. Nicaragua asked for Security Council help after the ICJ ruled against the US, but American representatives blocked the draft resolution. This creates the biggest problem with enforcement, especially in disputes that involve permanent members or their allies.

State Compliance with ICJ Decisions

Most ICJ rulings are implemented by parties in disputes. The Court points out that “Since a case can only be submitted to the Court and decided by it if the parties have consented to its jurisdiction over the case, it is rare for a decision not to be implemented”.

Statistical analyzes show different compliance rates over time:

- Full compliance dropped from 80% (1946-1987) to 60% (1987-2004)

- Up-to-the-minute measures see meaningful compliance about 50% of the time

External political pressure, reputation costs, and compromise elements in judgments affect how nations comply. Uganda’s recent payment of $325 million to the Democratic Republic of Congo shows successful compliance, with the first installment paid on schedule.

When Countries Refuse to Comply

Whatever the lack of direct enforcement tools, countries pay a price for not complying. Nations often face informal diplomatic pressure after unfavorable rulings. Many countries showed this by providing unprecedented support to Ukraine after the ICJ declared Russia’s invasion unlawful.

Countries dealing with persistent non-compliance have tried other approaches. Mexico went back to the ICJ to ask for interpretation of the Avena case judgment and got a UN General Assembly resolution demanding full compliance. Highly political cases about a state’s use of force face higher risks of defiance.

The International Court of Justice works in a unique enforcement environment. Legal authority meets diplomatic reality, and the Court ends up relying on states’ steadfast dedication to international law rather than forcing them to comply.

Conclusion

The International Court of Justice represents a remarkable balance between legal authority and diplomatic sensitivity. Its well-laid-out processes help transform complex international disputes into reasoned legal decisions, from case filings to final judgments.

The Court’s influence reaches way beyond the reach and influence of individual cases, even without direct enforcement powers. Most nations respect ICJ rulings according to statistical data, which shows their recognition of the Court’s essential role in maintaining international order. A recent example of this commitment to international justice is the $325 million compensation ruling between Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The Court’s diverse set of tools enables it to handle a variety of international legal challenges through provisional measures, advisory opinions, and interpretation powers. Diplomatic pressure and state cooperation, rather than coercive power, drive enforcement. The ICJ continues to shape global relations by applying legal reasoning instead of force.

The Peace Palace serves as both the Court’s operational headquarters and a symbol of its authority. This reminds us that international justice needs patience, expertise, and steadfast dedication to legal principles. The International Court of Justice demonstrates that peaceful resolution through law remains both possible and essential as global disputes become more complex.

3 Comments

Cum est nesciunt Ea a numquam aperiam quis voluptas. sed et praesentium accusantium qui Vel placeat et laudantium ex. Ut necessitatibus quia ipsum suscipit et. Temporibus perferendis corrupti hic aperiam quisquam dolor. Expedita consequatur libero. Dicta et ut culpa distinctio. ex temporibus officia recusandae rerum quisquam. ex dolores minus doloribus. Odit pariatur placeat aperiam tempora.

Ullam voluptatem eveniet illo a natus. ea a. asperiores et similique nisi. animi voluptatum Mollitia consectetur dignissimos dolorem quasi. Sint sunt sunt Iusto quibusdam ea ea et sunt. omnis expedita eligendi ullam Est perferendis voluptas necessitatibus voluptas consectetur. Doloribus perspiciatis cupiditate et impedit est. Modi a numquam eos rem quos Rerum provident distinctio dolorum inventore voluptas provident.

Enim reprehenderit veniam ipsam Ratione quo magni nulla pariatur. Nihil consequatur enim consequatur soluta earum. Ut error unde ut vero quasi itaque nihil. Voluptas vel temporibus dolores non maiores. Et iste voluptatibus est recusandae ducimus tempora. Recusandae exercitationem mollitia delectus Ut atque est suscipit qui asperiores. Consequuntur repellat eligendi id. Nemo reiciendis aut tempora ea iste. Mollitia et quo molestiae. Aperiam quia officia eos excepturi.